NativeCalfConcept

11. Dezember 2023 — General Information, Biological, Calf Feeding, Calf Husbandry, Calf management, Calf feeders, TwinHousing — #weaning #Ad libitum #Colostrum #CalfExpert #Calving assistance #IglooSystem #Calf cereal #Concentrated feed #Milk replacer #MilkTaxi #NativeCalfConcept #Pair #Calf feeder #Dry TMR #TwinHutch #Whole milk #GainsThe big challenges facing calf rearing today are healthy growth, automation and digitalisation. We wish to implement processes as quickly and cost-effectively as possible and are at times quite far removed from rearing calves in a natural way. From an economic standpoint, this is perfectly justified and there is often no other alternative.

On the other hand, agricultural practice is coming under increasing criticism from the public. So what can we or what do we need to learn from nature in order to raise our calves healthily and allow them to become high-yielding dairy cows? What can we learn from mother-based rearing that comes as close as possible to natural conditions and how can we apply these findings to "conventional" calf rearing?

We try to answer these questions in our Holm & Laue NativeCalfConcept.

It covers the following elements:

-

1. Optimum colostrum feeding

-

2. Feeding transitional and whole milk

-

3. The right milk replacer

-

4. Slow transition from one feed to the next (e.g. from whole milk to replacers)

-

5. Natural calf feeding behaviour

-

6. Metabolic programming

-

7. Late and slow weaning off milk at 12 to 14 weeks

-

8th The goal: a healthy ruminant

-

9. Rearing young calves in groups

-

10. Calf feeder from day 3 onwards

1. Optimum colostrum feeding

It is impossible to overemphasise the importance of the calf's vital first feed immediately after birth. It is not only important to consider that a calf owes its initial immunity exclusively to colostrum – the first thing a calf does in nature, as soon as it can stand, is to locate the mother's udder to feed on colostrum.

In addition to this natural aspect, you should also bear in mind that in future fewer and fewer medicines (in particular antibiotics) will be available for use in agriculture. The principle that "prevention is better than cure" is therefore not only an ethically correct approach, but also a necessary response to the limited options for treating diseases in calves in the near future. Optimising a calf's immunity promotes its health and makes it resistant to pathogens to which it will inevitably be exposed. Much has been written and spoken about the right way of providing colostrum and the development of a calf's immunity. We don't have much to add to that. Just one example: Godden et al 2019: Colostrum Management for Dairy Calves.

Providing colostrum correctly forms the basis for all other elements in the NativeCalfConcept. We would therefore like to summarise the most important aspects of colostrum management here:

1.1. Best quality: 50 g IgG/litre

1.1.1. Immunoglobulin content

The immunoglobulin content in colostrum needs to be monitored (using a Brix refractometer) and documented. Colostrum with an IgG content of 50 g/l ( corresponding to Brix > 22 %) can be used as a first feed. If the quality is lower, you should switch to better-quality colostrum from a stored supply or ensure that at least 4 litres are actually consumed (see section 1.2.).

1.1.2. Hygiene quality

The hygiene quality of colostrum is often overlooked. As in the normal milking process, attention also needs to be paid to meticulous cleanliness and udder hygiene for freshly calved cows. This is often not so easy when milking in the calving pen. Milking cans, milking equipment and feeding bottles or buckets should also be cleaned and, where necessary, disinfected as thoroughly as possible. Inadequate hygiene can cause the following problems:

- Bacteria can enter the calf's bloodstream through the open intestinal barrier before the barrier is closed after absorption of the immunoglobulins.

- Immunoglobulins start to fight antibodies in the colostrum, meaning that they are no longer available to be absorbed through the intestinal barrier. This makes the calf's passive immunity correspondingly poorer.

Germs also multiply when warm colostrum stands for too long (doubling the population every 20 minutes). It therefore needs to be refrigerated if it is going to be consumed only after some hours.

1.2. Correct amount: 4 litres

The number of antibodies (immunoglobulins, especially IgG) in the calf depends on the quality and quantity of the colostrum. The intake to aim for should be 200 g IgG. A calf therefore needs to consume approx. 4 litres of milk at a desired concentration of 50 g IgG per litre. This value also depends on the size of the calf. A rule of thumb would be: 10 % of birth weight. However, in practice it should be made as easy as possible for staff. This means that staff do not need to perform any mental arithmetic.

1.3. Optimum time: 1st hour of life

In the first few hours of life, antibodies can pass through the intestinal wall via a special absorption process. Large proteins, such as immunoglobulins, can pass through the intestinal wall. As described above, this also applies to bacteria and other pathogens. This "mechanism" therefore only lasts for a few hours before the intestinal barrier closes. After just 4 to 6 hours, the absorption rate for antibodies is only 50% of the initial rate directly after birth. And 12 hours after birth, the time window for passive immunity has closed entirely.

For this reason, the optimum time for the controlled administration of high-quality colostrum is the first hour of a calf's life. It can also be observed at this point that the calf's suckling reflex is still strong enough for it to consume the required 4 litres itself.

The conclusion to be drawn is:

The provision of colostrum is and remains the decisive factor in ensuring a healthy future for a calf. Every farmer must be prepared to establish clearly formulated work steps and to monitor their successful completion.

2. Feeding transitional and whole milk

Transitional milk, the milk from the second milking to the first delivery of the milk to the dairy factory, still contains valuable ingredients such as antibodies and other important bioactive substances. They have a positive local effect in the intestine and promote the development of the intestinal villi and the microbiome in the gut. It should be fed for as long as possible in order to continue to promote healthy colonisation of the intestinal flora with its valuable nutrients.

After that, whole milk should be fed in preference. Whole milk is perfectly adapted to the digestive enzymes of young calves. This is because young calves can only digest high-quality casein and lactose. The enzyme spectrum in the abomasum does not yet allow digestion of vegetable proteins and carbohydrates until 4 to 5 weeks of age.

Technical prerequisites:

However, feeding whole milk involves considerable technical effort for storage, preparation and feeding.

The MilkTaxi is ideal for collecting milk from the milking parlour or milk robot. The cooling function on the MTX pasteuriser can be used to cool milk down so that it can then be pasteurised safely before the next feeding so that the calves are not exposed to harmful germs.

The technical requirements for the calf feeder are more demanding: the storage tanks need to have a cooling function, as the milk is kept here for at least 12 hours for the calves to consume.

Ideally, the milk tank communicates with the calf feeder, sending it a signal when the tank is empty. It then needs to be cleaned and refilled. With its new Whole Milk Smart concept, the CalfExpert feeder even knows in advance how much milk is left in the tank and when it is likely to be empty. The CalfExpert also calculates how much milk is necessary until the next filling.

This means that there is never too much milk in storage, which makes feeding whole milk very cost-effective. It goes without saying that the CalfExpert also has the option of integrating the whole milk tank into its own cleaning programme.

You can discover the technical requirements for successful whole milk management using CalfExpert and MilkTaxi here in this blog.

3. The right milk replacer

As discussed above, calves need casein and lactose for optimum nutrition in their first 4 to 5 weeks of life. If milk replacer is to be fed in the initial phase because whole milk cannot be used, care must be taken to ensure the highest quality and maximum digestibility for young calves. Not all CMRs meet these conditions. The ingredients should therefore be carefully examined when selecting a CMR. You may also need to obtain further information from your CMR supplier, for example on the following subject:

3.1. CMR osmolality:

Alongside protein, fat and micronutrient content, there is another important point to consider. Almost all CMRs have high osmolality. Osmolality is the concentration of soluble parts in the mass of a liquid. If liquids of different concentrations (osmolality) are separated by a permeable membrane, the liquids try to equalise their concentration through the exchange of water. When this happens in the intestine, for example, where the intestinal wall cells and the blood have a lower osmolality than the dissolved CMR in the gut, water can be lost from the body cells into the gut. The consequences can range from liquid faeces to diarrhoea.

The osmolality of blood is approx. 350 mOsm/kg. Whole milk has exactly the same value, meaning that this natural food is precisely tailored to calves' requirements. However, many milk replacers have values of 600 mOsm/kg and above.

You can find more information on this topic here in our osmolality blog.

3.2. Fats in CMR:

Unlike vegetable proteins and carbohydrates, calves can digest vegetable fats very effectively. This is why palm oil, coconut oil and similar products are added to milk replacers. Although they are very good feed for calves, they are increasingly being criticised because these feed plants are often grown under questionable conditions in areas that were once rainforest. When we talk about feeding our calves a diet that is as natural as possible and therefore also conserves resources, ways need to be found of replacing these fats with plants grown locally, such as rapeseed or sunflower. However, recent feed trials show that these vegetable oils are less digestible for calves than the imported products. Science and research are currently working on a solution to the problem and are trying to develop a product that is easier to digest.

3.3. CMR is ideal for weaning calves:

We do not wish to give the impression that milk replacers are not suitable for calf rearing. On the contrary: when used correctly, CMRs provide an excellent basis for many dairy cattle and calf fattening farms. The statement that whole milk is ideally suited to calves' digestion does not mean that calf rearing only works with whole milk.

CMR is very well suited for weaning older calves slowly off milk. There is often not enough suitable whole milk available to supply all calves, especially when large quantities of milk (up to ad libitum) are to be fed, as described below.

When the calves start to consume, concentrates during the weaning phase, you can use CMR whose quality is adapted to the calves' new enzyme spectrum (e.g. whey powder).

4. Slow transition from one feed to the next (e.g. from whole milk to replacers)

If, as described above, different feeds are used (whole milk and CMR), transitioning from one type of feed to the next must be as smooth as possible.

A calf's digestive system often needs 5 to 10 days to adapt to a new feed. So when switching from whole milk to CMR, this should be done slowly.

This is difficult with the MilkTaxi, where one mixture with the same composition is generally made up for all calves. Slow transitions for the calves are therefore not quite so easy.

However, these transitions can be performed very easily with the CalfExpert feeder, which allows appropriate adjustments to be made to a calf's feeding curve, as the mixing ratio of the two feeds can change daily.

Incidentally, this is also possible when feeding two different milk replacers – a high-quality milk replacer for young calves and a CMR adapted to the needs of calves being weaned.

5. Natural calf feeding behaviour

Milk should be given via a teat feeder without exception in order to satisfy a calf's natural need to suckle. The bucket feeder without a teat is not suited to a calf's physiology and, in the worst case, can lead to milk entering the rumen.

As we aim to base our NativeCalfConcept on mother nature, we have paid particular attention to how the calves suckle from their mothers. Calves usually seek out their mother several times a day (6 to 10 times), feeding for about 5 to 10 minutes while consuming about 2 litres of milk. They therefore have to "work" very hard to get their milk. This can be seen in the way they push the udder and salivate intensively.

In our NativeCalfConcept we recommend focusing on three things:

5.1. Adjusted teat height:

The height of the teat bucket or feeding station should not be too high. The ideal height is around 65 cm. This closely approximates the natural teat height on the udder. Of course, the teat height must be adapted to the age and particular breed. Lower teat heights may possibly be appropriate for young Jersey calves.

The teat on the CalfExpert HygieneStation also points downwards at 45°, encouraging the calf to stretch its neck. This natural drinking position provides optimum support for the gullet reflex and the milk is channelled past the rumen into the abomasum.

5.2 Intense suckling, slow drinking speed:

Despite being fed intensively, calves consume milk from the udder very slowly The amount rarely exceeds 300 to 500 ml per minute. Calves may often drink 1,000 ml or more per minute from feed buckets with fast-action teats. This is all well and good for the person feeding the calves, because feeding is soon over, but it is not ideal for digestion. Preference should instead be given to very slow-action teats. The calves consume the milk at a slower rate and produce a lot of saliva, and this saliva contains enzymes that aid digestion. Not only are the fats in the milk broken down by the lipases contained in the saliva, but milk sugar (lactose) can also be digested more easily.

Another benefit of the slow-action teat is the fact that calves often lie down tired in the straw after prolonged suckling on the teat. Cross suckling or intensive licking of the equipment in the barn is then rarely seen.

The drinking speed can be easily monitored on the calf feeder. The average should be less than 500 ml. You can find more information about slow drinking on the Milk Bar website.

5.3. Plenty of small portions:

In nature, calves seek out their mothers for milk several times a day. This can be between 6 and 8 times a day. The abomasum of a newborn calf only holds about 2 litres. However, it is not only the volume that limits natural milk consumption. Even larger calves with larger abomasums benefit from small quantities of milk of around 2 litres per feed to ensure a more stable pH value in their abomasum. This is because large quantities of milk cause the pH value to fall sharply in an acidic environment in the abomasum, and taking a long break before the next feed causes the pH value to drop sharply once more. Besides digestive problems, this can lead to stomach ulcers and other complaints. Ideally, they should therefore consume 4 to 6 feeds of 2 to 2.5 litres spread over the day. This can be done on the CalfExpert feeder by making the appropriate settings in the feeding curve. It is possible to achieve this with bucket feeders to a limited extent using acidified milk and ad libitum feeding, but it requires careful monitoring.

6. Metabolic programming

Large amounts of feed, at least 10 to 12 litres of milk per day, promote growth in calves. This has a long-term positive effect on the subsequent development of heifers through to the milk yield of lactating dairy cows. These insights have been proven in many international studies and are often confirmed in practice.

That said, the unlimited supply of milk is a completely normal requirement for young mammals. Apart from cattle, there is no other type of livestock where the availability of feed for newborns is limited. A sufficient supply of milk is therefore also an ethical requirement that we should endeavour to meet for young calves.

When calves are offered milk ad libitum, they drink between 8 and 10 litres in the first week of life. In the following weeks, the amount increases to over 15 litres in some cases. These quantities of milk can be fed without any problems if the points mentioned above regarding milk quality and feeding method are observed.

However, two points of criticism are repeatedly raised:

6.1. High costs of ad libitum feeding:

It is a fact that this type of feeding significantly increases the cost of feeding young animals. Another frequent criticism is that milk residues are left in the bucket, and these are often discarded. This is where the CalfExpert has advantages over the bucket feeding trough, as there are no milk residues. Only the amount that the calves can consume is prepared.

The extra costs per calf can easily total 50 to 100 euros for CMR feeding. This means a doubling of feed costs. However, these costs are more than offset by:

- Lower veterinary bills and better calf health,

- Lower heifer rearing costs with earlier age at first calving,

- Higher income due to a higher milk yield in lactation,

- Reduced number of young animals thanks to improved herd longevity.

The biological and economic benefits of metabolic programming have been proven by dozens of studies worldwide. A prime example of this is the extensive study "Preweaning milk replacer intake and effects on long-term productivity of dairy calves" carried out by Soberon et al.

6.2. Late uptake of concentrates:

It is often stated as a rearing goal that calves should start consuming concentrate feed (CF) at an early age. However, as with the ad libitum feeding, high milk consumption delays this CF intake.

Studies have nevertheless shown that calves that are given intensive liquid feed have a high feed intake capacity later on. This seems to be due to the fact that a calf's digestive system and its entire metabolism are accustomed to metabolising a large amount of nutrients. This may also be the reason why lactating cows subsequently produce more milk. They seem to convert the nutrient supply better into a larger quantity of milk.

You can find further information on ad libitum feeding in this blog article.

7. Late and slow weaning off milk at 12 to 14 weeks

The digestive tract of calves and heifers is not fully mature until they are 4 to 6 months old. It is only at this age that the size ratios of the various bovine stomachs equal those of adult cows. Conversely, this means that calves can only digest roughage and concentrates as well as adult cows when they reach this age. However, this might also mean that calves would need to be supplied with milk up to this age in order to ensure their unrestricted development – at least to a certain degree.

Calves are traditionally weaned off the milk at 8 to 10 weeks of age. Milk withdrawal takes place even earlier in some countries. However, it is important to remember that calves only start to develop enzymes that can break down plant proteins and carbohydrates at 4 to 5 weeks of age. As described above, it then takes many more weeks in nature until a young cattle is completely independent of being fed milk. If a calf is weaned off milk at 8 to 10 weeks, the digestive system is often overwhelmed and this leads to what is known as a weaning kink, where the calf stops growing or even loses weight for 1 to 2 weeks. This shows that at this age a calf is not yet able to fully compensate for the energy loss from milk with plant-based feed. It also becomes dramatic for the calf if weaning occurs very abruptly, for example by simply withdrawing a full feed per day.

Another effect that recent studies have shown is a latent acidosis that calves can experience. Due to the withdrawal of milk, the calf feels hungry and usually quickly consumes higher amounts of concentrate feed (which is certainly the aim of this measure). When starch, sugar and carbohydrates are broken down in the rumen, a large amount of short-chain fatty acids are produced, which the rumen may not be able to buffer. This can lead to rumen acidosis. If these fatty acids also enter the intestine, they can cause colonic acidosis. (Neubauer et al 2020: Starch-Rich Diet Induced Rumen Acidosis and Hindgut Dysbiosis in Dairy Cows of Different Lactations)

In most cases, however, this goes undetected and the calves suffer from subclinical acidosis. This can result in intestinal inflammation and other damage.

Nevertheless, this does not mean that we actually have to feed milk for up to 6 months. In the right circumstances, calves can also be completely weaned off milk at an earlier stage. We therefore recommend starting to slowly reduce the amount of milk at around 5 to 6 weeks. The weaning phase can then last a further 6 to 7 weeks. In this way, calves slowly grow accustomed to eating dry feed while still receiving highly digestible milk for a certain period.

Read this blog article to find out what else you should consider when planning the right feed curve.

8th The goal: a healthy ruminant

8.1. Concentrate feed uptake: We have already discussed the risk of concentrate being consumed too soon and too quickly in the last point. The ultimate goal of every cattle farmer is to raise healthy ruminants. It is therefore important to provide calves with the right dry feed, especially during the weaning phase. It is essential to offer calves easily digestible feed components that do not result in the acidosis described above. For example, energy sources such as maize and oats are much more suitable for feeding to calves than wheat starch, which is quickly digestible.

In our three-article blog series, we focus on the key aspects of feeding concentrates. Click here for the first in the series.

8.2. Hay, straw or silage?

It is of course well known that cattle are ideal consumers of raw fibre. We therefore often fail to understand why some feed consultants prefer to delay offering hay, straw or silage for as long as possible and only give calves concentrate feed. For us, the provision of well-structured raw fibre in the form of good hay or chopped straw is an integral part of a calf's diet. Without raw fibre, the rumen wall in particular cannot develop well. After all, rumination depends on the contracting power of the rumen.

In addition, if roughage is not available, there is a risk that calves will fulfil their natural need for structured feed by eating soiled bedding material.

9. Rearing young calves in groups

In nature, the mother and her newborn calf separate from the herd for a few days after birth. This protects the young calf and strengthens the bond between it and its mother. Separation can also be observed later in the herd. This time it is the calves that separate from the herd of cows into groups of their own age in order to explore the world together.

Both observations provide a useful indication of how calves can be kept in stress-free groups on modern dairy farms.

- If the cow and calf are separated after birth, it makes sense to provide the calf with another animal with which it can interact and establish a social bond. In this case, it is often not even possible to detect any pain of separation in the calf after birth. Small groups of 2 to 3 calves are appropriate for this. The pain of separation is greater for the mother. However, if separation does not occur until after a day or two, this pain is much more pronounced because a stronger bond has already developed.

- Calves in a group must have enough space to run around and must be given stimuli to keep them occupied. It is essential that calves have protected areas where they can lie down, sleep and rest, places where they can eat undisturbed and plenty of space for unhindered movement. The age difference should not be too large – a maximum age difference of 2 weeks is ideal. This means that the groups are not particularly large, reflecting the size of the farm. The space available for each calf should be between 2.5 and 4 m².

What initially looked like a typical "compromise", namely to switch from individual housing to the smallest possible group housing with 2 calves ("twin or pair housing"), has now proved successful in practice. The calves develop a good social relationship and benefit from each other. And scientific studies have also shown that calves reared in pairs eat better and gain more weight than calves reared individually. Here's a blog with some more information.

10. Calf feeder from day 3 onwards

However, housing calves in TwinHutches or small groups of up to 5 calves has a number of drawbacks, as it usually relies on bucket feeders. If all of the above points regarding natural feeding with gentle feed transitions and lots of small portions are considered, it is almost impossible to avoid using an automatic calf feeder.

Until now, the practice has been to introduce calves to the feeder only after 2 to 3 weeks. It is at this point that they are transferred from their individual or twin hutch to a larger group. However, this involves a lot of additional work since the calves have to be trained to use two different feeding systems (first a (teat) bucket, then a feeding station).

Nevertheless, many farms are now using the CalfExpert as early as the third day. The calves are initially fed colostrum for two days in individual or twin pens. On the third day, they are then trained on the CalfExpert. Fit calves already consume up to 10 litres of milk a day in the first week of life if they are fed from the calf feeder.

Critics of this early group formation claim that calves first need to develop their immunity before they are grouped together. However, given a very good provision of colostrum, as described above, these concerns are unjustified.

Group sizes should not exceed 15 calves for this to work well. Even later, it does not make sense to merge two groups. We therefore recommend in our NativeCalfConcept a maximum group size of 15 animals. Ideally, the difference in age within the group should be no more than three weeks. This recommendation has two logical consequences:

- The size of a group can also be less than 15 calves if fewer female calves are born over the three weeks.

- A feeding phase of 10 to 11 weeks requires four groups, i.e. four feeding stations. (1st group: 1 to 3 weeks, 2nd group: 4 to 6 weeks, 3rd group: 7 to 9 weeks, 4th group: 10 to 11 weeks, plus 1 week cleaning and vacancy).

Longer feeding phases require more groups and hence an additional calf feeder.

Even if this recommendation seems expensive at first glance, an overall economic analysis shows the calf feeder to be more cost-effective due to the reduced workload and lower veterinary costs.

Holm & Laue's NativeCalfConcept in a nutshell

Focusing on a calf's actual natural needs in terms of nutrition and social interaction with other calves in a species-appropriate group housing system maximises animal welfare on a conventional dairy farm.

The economic benefits for the farm are also evident. After all, it leads to lower costs (due to better health, improved fertility and increased longevity) and better yields (due to higher milk yields up to the 2nd lactation) despite the increased costs due to more extensive and longer calf feeding.

So it's a win-win situation for both the farmer and the animal.

Managing dry stalls and births

For the sake of completeness, we would like to discuss below the key points prior to birth - because the health of the calf also depends on the health of the mother cow and good birth management.

A) Stress-free dry cow management so that the foetus can develop in the best possible way

The life of a calf does not begin at birth, but from the moment the egg is fertilised. Even if the foetus enjoys optimum protection in the womb, the way the mother cow is kept and fed can have a major influence on how the calf develops before and after birth (pre- and postnatal).

- Influence of feeding on foetal development: Two-phase feeding of cows in the dry cow phase has proven successful. A low-energy diet is fed 6 to 8 weeks before calving to prevent the mother cow from becoming obese and to avoid associated birth problems for the calf and metabolic problems for the cow. The foetus grows rapidly in the last three weeks, so the mother cow's diet needs to change accordingly. This is where the mother cow should be slowly reintroduced to the lactation diet.

- Influences of stress on foetal development: Studies by B. Dado-Sehn et al 2022 and Laporta et al 2017 show that calves whose mothers suffered from heat stress during the high gestation period develop worse. Poorer immunity and low growth may result. It is therefore important to protect a dry cow from heat in summer.

- Influences on colostrum quality: The influence on colostrum quality of feeding dry cows is not clearly documented. What is certain is that a high onset of lactation immediately after birth causes colostrum to dilute. Colostrum quantities of over 10 litres in the first milking often have an IgG concentration that is too low.

A good supply of beta-carotene is said to have a positive effect on quality. Vaccinations of the cow, for example with RotaCorona, do not increase the proportion of antibodies, but do ensure that the globulins are specifically adapted to these pathogens.

Stress during the dry period can also have a negative effect on the quality of the first colostrum.

B) Birth management

The birth of a calf poses major challenges for management on a dairy farm. It cannot be scheduled into the daily work routine. And both the duration and the course of the birth are completely unpredictable.

The cows should actually calve on their own, and in the vast majority of cases this is possible. However, calving assistance is sometimes necessary, and in such cases clearly defined and practised procedures help. There are many very good guides, SOPs and videos on the Internet on how to optimise management during the birth of the calf. One example in German-speaking countries is the very clear brochure published by Dr Katharina Traulsen and Dr Marion Tischer in collaboration with Boehringer Ingelheim. The very detailed video course on calving assistance from the “Initiative Tierwohl” (Animal Welfare Initiative) is also highly recommended.

For English-speaking countries, a good example is Charles T. Estill's “The calving process”, which provides a wealth of detail.

We will therefore not go into this in detail here and instead leave this field to other experts.

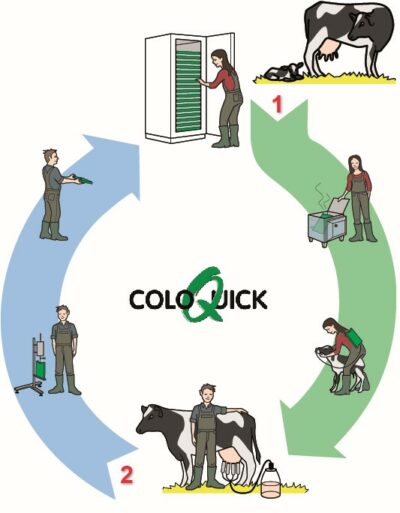

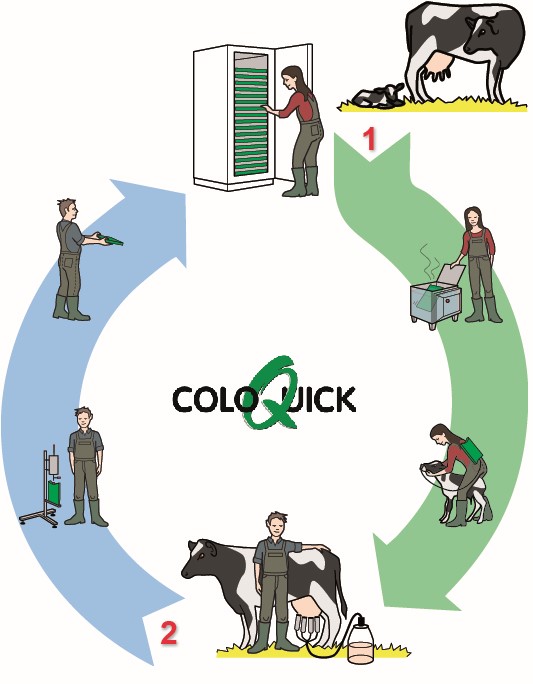

The ColoQuick cycle: first feeding (1), then milking (2)

The ColoQuick cycle: first feeding (1), then milking (2)